ここからコンテンツです。

How organic chemistry can contribute to society

Applications of recent advances in research, such as in drug discovery and pesticide detectionSeiji Iwasa

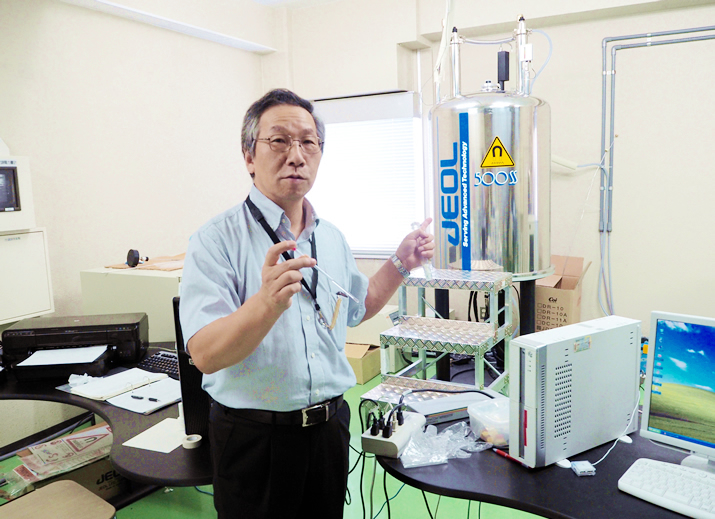

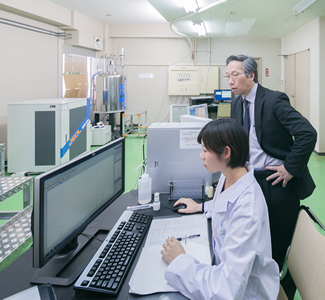

Professor Iwasa’s research involves studying and synthesizing organic compounds and devising ways to use those compounds in the fields of medicine and health, such as molecular sensors. Specifically, he extracts various organic compounds produced in nature and determines their molecular structures, and synthesizes useful biologically active compounds by freely manipulating the bonds of organic compounds. As synthesizing useful organic compounds with complicated molecular structures in large batches quickly can be helpful in areas such as drug discovery and food safety, this high-profile field of research has been widening its scope of applications in recent years.

Interview and report by Interview and report by Madoka Tainaka

Determining the structures of natural products and achieving total synthesis

Professor Seiji Iwasa became interested in the world of organic compounds as a result of his fascination with the miraculous properties of medicinal herbs and other natural products. After that point, guided by his curiosity, he worked toward becoming a researcher in natural products chemistry.

Professor Iwasa says, “Just as Ninjas once used aconite poison as a weapon by wiping it on the tips of their Shuriken, there are many surprising natural products in this world that can take a person’s life even when used in tiny quantities. However, aconite also has beneficial cardiotonic and analgesic effects, and thus has long been used as a medicine as well. That shows that even poison can be a medicine if used properly. Nevertheless, in order to use such products effectively, we need to understand their structures and functions. It is the mission of organic chemists to make these products useful by reproducing them synthetically, a process which is called ‘total synthesis’.”

At that time, Professor Iwasa was working on the total synthesis of strychnine, an extremely toxic alkaloid. The molecular structure of strychnine was uncovered in the mid-20th century after a century of effort. After that discovery, R.B. Woodward et al. succeeded in completing the synthesis of strychnine in 29 steps. Professor Iwasa and his team successfully shortened the process by more than half, to just 12 steps. This was in 1994.

“The method we used is called retrosynthetic analysis, and it involves exploring how to synthesize a substance by breaking down the synthetic process step-by-step while analyzing the molecular structure. This method allowed us to more easily synthesize strychnine. This field deals with molecules, which have a three-dimensional form. Because of this, it requires big leaps in topological thinking and mathematical sense. That is why this research is so thrilling to me,” says Professor Iwasa.

Catalytic asymmetric reactions: A promising tool for drug discovery

In order to seriously investigate the methodology for further shortening and simplifying the process of total synthesis, Professor Iwasa is currently focusing his efforts on the development of catalytic asymmetric synthesis. Asymmetric synthesis is a method of synthesizing optical isomers, which has come to be used in the development of most drugs in recent years.

Professor Iwasa explains the concept. “An optical isomer is a compound that cannot be superimposed on its opposite compound, like a human’s right and left hands. In essence, it is a mirror image of a substance. In the case of most optical isomers, the right-handed one has a therapeutic effect, whereas the left-handed one is toxic. Even though the substances look the same, they have completely opposite physiological properties.”

One well known example of this is thalidomide. Thalidomide, a drug developed as a hypnotic and sedative, caused a global tragedy in 1957 due to the toxicity of one of its isomers, which caused the children of mothers who took the drug while pregnant to be born with limb malformations. When normal methods of synthesis are used, both the right-handed and left-handed optical isomer are produced at the same time. Essentially, this tragedy occurred because both isomers were present in the drug. Therefore, in order to safely use an optical isomer as a drug, it is necessary to skillfully produce just the isomer with the useful properties. This can be done by asymmetric synthesis.

Professor Iwasa developed a method for performing these reactions using an unstable carbene intermediate and an organometallic complex. This acts as a highly active catalyst because of the electrical properties of the metal. When this is combined with the asymmetric environment of the organic ligand, just one optical isomer of the substance is produced selectively. This is what is called a ‘catalytic asymmetric reaction’. Actually, the first person to use a metallic complex as a catalyst in asymmetric reactions was Dr. Ryoji Noyori, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2001.

“To give an analogy, an asymmetric reaction is like setting out a glove that will only fit the left hand, so that it will only recognize the left hand. For example, a substance called chrysanthemic acid that is used in mosquito coils is also an optical isomer, and is efficiently synthesized through an asymmetric reaction catalyzed by metal. The trick is that using a complex formed from an organic metal with high electron density and a highly configurable ligand as a catalyst makes it easy to control the reaction.”

In recent years, Professor Iwasa has also incorporated computer science into his research. He has started a project to explore reaction mechanisms regulated at different intensities by analyzing reaction mechanisms through simulations. He has also branched out to working on making catalysts non-toxic after use in chemical reactions.

“I believe that my job is to create new fields within organic chemistry and to keep expanding their reach.”

A wide scope of work ranging from molecular sensors to development of drug substances

One of Professor Iwasa’s achievements, that exemplifies the wide-ranging scope of his research, is his project to develop a kit for testing for residual pesticides using immunochromatography. He worked on this project as part of the Food Safety Technology Project, one of the core research projects of Knowledge Hub Aichi, which is run by the Aichi prefectural government. It involves the simple detection of residual pesticides by employing antibody reactions, which are part of organisms’ immune systems, a field of study quite different from total synthesis.

“Testing devices have conventionally been large and expensive, require trained specialists to operate, and take a long time to run tests. Our goal for this project was to develop a low-cost system that is convenient and fast to use in places such as manufacturing plants and overseas. That is why we turned our attention to organismal immune systems.”

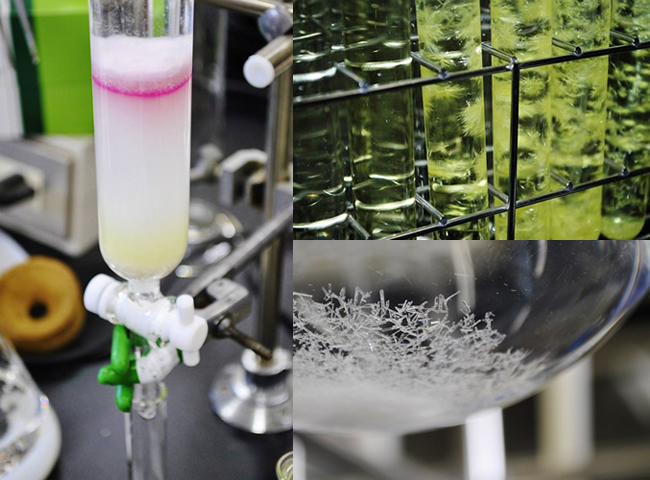

However, pesticide molecules are too small to elicit an immune response without alteration. Therefore, Professor Iwasa made the pesticide molecules bigger by attaching a massive protein extracted from shellfish, and experimented by injecting those molecules into mice. The mice recognized the molecules as foreign bodies and produced countless antibodies. Antibodies against the pesticide are sorted out from amongst those antibodies and fused to detoxified cancer cells to promote proliferation. Essentially, Professor Iwasa made antibodies against pesticides proliferate endlessly by exploiting the properties of cancer cells.

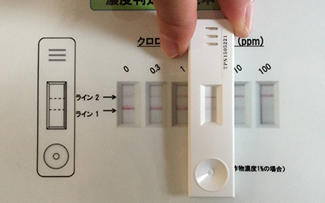

“When antibodies produced in this way are planted onto gold colloid, which acts as an antibody label, and a solution containing the pesticide is run across it, an immune response is elicited. This kit determines the concentration of pesticide by measuring absorbance,” Professor Iwasa explains.

He has created two different kits; a kit like a pregnancy test for simple visual confirmation, and a quantitative kit that uses optical equipment, so that they can be used for different purposes. He says that he is now working on how to make these into products.

In addition to this work, he has developed a method for extracting a useful substance from Melaleuca leaves in a joint project with Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology in Vietnam. This substance is already being used as a drug substance. Professor Iwasa says that while conducting this research, he traveled by canoe into Vietnamese forests with thick-growing Melaleuca groves.

“Curiosity has always been what has driven my research. As long as I have curiosity, I can go anywhere. Even still, I felt a bit scared in the forest in Vietnam.” It seems that Professor Iwasa’s curiosity still has no limit.

Reporter's Note

After finishing his degree at Chiba University, young Professor Iwasa wrote letters to research institutions all over the world telling them of his desire to pursue the study of organic chemistry. He got his first response from the University of Ohio, despite having no connections there. He then went to the United States, where he achieved several research accomplishments, including the synthesis of strychnine, and later got an offer from the University of Chicago. This moment made him feel how open-minded Americans are and how strong their researcher network is.

In order to return the favor, Professor Iwasa is making an active effort to recruit international students. Students from eight different countries, including China, Mongolia, Laos, and Malaysia, are currently working with him in his laboratory.

“Learning about the world like that has reminded me of what is good about Japan. I want to bring good aspects of Japan such as its advanced technological capabilities, strong morality, and respect for the environment to the rest of the world. To that end, I am currently engaged in Japanese language education in Asia as well,” says Professor Iwasa.

His curiosity is extending beyond his research to education and the environment as well.

創薬や農薬の検知など、有機化学の先端研究で社会に貢献する

岩佐精二教授の研究は、自然が生み出すさまざまな有機物質を抽出し、分子構造を解き明したり、また有機化合物の結合を自在に操ることで、有用な生理活性物質を合成したり、分子センサーとして応用するなどして、医療や健康に役立てるというもの。複雑な構造を持つ有用な有機化合物を大量かつスピーディに合成できれば、創薬や食の安全などに役立てられるとして、近年、その応用範囲を広げつつある注目の研究分野である。

天然物の構造を明らかにし、全合成する

岩佐精二教授が有機化合物の世界に興味を抱いたのは、薬草などが持つ驚異の力に魅せられたのがきっかけだった。

以来、好奇心に導かれ、「天然物化学」の研究者の道へ進んだのだという。「かつて忍者が、トリカブトの毒を手裏剣に塗って武器として利用していたように、世の中にはほんのわずかな量でも命を奪うような驚くべき天然物があります。一方でトリカブトには強心作用や鎮静作用があるとして、古くから薬としても用いられてきたように、毒もうまく使えば薬になる。ただ、それらを有効に使うためには、その構造と機能を明らかにする必要があります。さらにそれらを人工的につくり出す、すなわち全合成をして役立てるのが天然物化学の使命です」と岩佐教授は語る。

そうした中、かつて岩佐教授が手がけたのが、ストリキニーネと呼ばれるアルカロイド系の毒性が非常に強い物質の全合成だった。ストリキニーネの分子構造は20世紀半ばに1世紀かけて明らかにされたもので、その後、Woodward,R.Bらが37ステップによる全合成に成功。それを岩佐教授らは半分以下の12ステップに縮めることに成功したのである。1994年のことだ。

「逆合成解析と言いますが、分子構造を分解しつつ、ステップごとのパーツに分けて合成の仕方を探るのです。これにより、より簡単にストリキニーネを合成できるようになりました。この分野は、分子という三次元の形を扱うことから、ある意味、位相幾何学的な発想の飛躍と数学的なセンスが必要であり、そこに研究の醍醐味があります」と岩佐教授は言う。

創薬で期待される「触媒的不斉反応」

さらに、全合成をより短く、簡便にできないか −- その方法論を突き詰めるために、現在、岩佐教授が注力するのが「触媒的不斉反応の開発」である。不斉反応とは、近年、ほとんどの医薬品に利用されている光学異性体を合成するための手法の一つだという。

「光学異性体というのは、人間の右手と左手のように、重ね合わすことができない化合物のこと。つまり、鏡写しの関係にある物質です。光学異性体の多くは、右手系は薬として有用でも、左手系は毒性を持つといった具合に、同じように見えても、その生理活性はまったく異なります」と岩佐教授は説明する。

その一例として有名なのがサリドマイドだ。1957年に睡眠鎮静薬として開発されたサリドマイドの片方に毒性があったため、この薬を服用した妊婦から生まれた胎児に四肢欠損が生じるという、世界規模の悲劇が起こった。通常の合成法を用いる限り、右手系・左手系の光学異性体は同時に生成されてしまう。つまり、両方が含まれていたことに原因があった。したがって、光学異性体を薬として安全に活用するためには、有用な機能を持つ片方だけをうまくつくり分けなければならないのだ。その片方だけをつくり分けるのが不斉反応である。

その際、岩佐教授は不安定なカルベン中間体と有機金属錯体を利用し、金属が持つ電子的な性質を利用して活性の高い触媒として用い、有機配位子の不斉環境と組み合わせることで、選択的に片方の物質だけをつくる手法を開発した。これがすなわち、「触媒的不斉反応」だ。じつは、不斉反応の触媒として金属錯体を最初に採用したのは、2001年にノーベル化学賞を受賞した野依良治氏らである。

「たとえるなら、不斉反応というのは左手だけにフィットするようなグローブを用意してあげて、左手だけを認識させるというもの。たとえば、蚊取線香に使用される菊酸という物質も光学異性体で、金属を触媒とした不斉反応により効率よく合成されています。電子密度の高い有機金属と微調整可能な配位子からなる錯体を触媒として使うことで、反応がコントロールしやすいところがミソなんですね」

岩佐教授は近年、計算機科学を取り入れて、シミュレーションで反応機構を解析することにより、さまざまな高度に制御された反応機構を探る取り組みも始めている。さらに化学反応後の触媒の無害化にも手を広げる。

「有機化学の新たな領域を創出し、射程距離を広げていくのが私の仕事だと思っています」

分子センサーや医薬品の原料開発まで幅広く

その岩佐教授の幅広い研究を象徴する成果の一つが、「イムノクロマト法による残留農薬検査キットの開発」である。これは、愛知県が推進する「知の拠点あいち」重点研究プロジェクトの一つ、食の安心・安全技術プロジェクトの一環として取り組んだ研究で、残留農薬の検知を、生物の免疫システムである抗体反応を活用して簡便に調べるというもの。全合成とはかなり違う分野の研究だ。

「従来の、検査機器は大型で高価なうえ、熟練した専門家が必要で検査に時間を要するものが多かったのですが、ここでは生産現場や海外などで簡便に素早く使える安価なシステムを目指しました。そこで目をつけたのが、生物の免疫システムです」

しかし、農薬の分子は、そのままでは小さすぎて免疫応答を起こさない。そこで、農薬に貝から抽出した巨大なたんぱくをつけて大きな分子にし、これをマウスに投与した。するとマウスはこれを異物だと認識して、無数の抗体をつくり出す。その中から農薬に反応する抗体だけを取り出し、さらにがん細胞を無毒化した細胞と融合させて、増殖させたのだという。つまり、農薬に反応する抗体を、がん細胞の性質を利用して無限に増殖させたわけだ。

「こうして生産した抗体を、抗体標識となる金コロイドに植え付け、その上に農薬が含まれた液体を流すと免疫反応が起こります。その吸光度を測ることで農薬の濃度がわかるというしくみです」と、岩佐教授は説明する。

キットは、妊娠検査キットのように目視で簡単に確認できるものと光学機器を使って定量的に測れるものを用意し、用途に応じて使い分けできるようにした。現在、製品化に向けて検討しているところだという。

そのほかにも、ベトナム・ホーチミン市工科大学と共同で、ユーカリの葉から有用な物質を抽出する方法を開発。医薬品の原料として、すでに活用が始まっている。その際は、ユーカリの樹が茂るベトナムの森までカヌーで赴いたこともあるという。 「研究を突き動かすのはいつだって好奇心です。それがある限り、どこへでも行きますよ。もっともベトナムの森では少々怖い思いもしましたが(笑)」

岩佐教授の好奇心は、まだまだとどまることを知らないようだ。

取材・文=田井中麻都佳

取材後記

千葉大学で学位を取った後、天然物化学を究めたいと、世界中の研究所に手紙を書いたという若かりし日の岩佐教授。そのとき、なんのコネもないのに、最初に返事をくれたのが、オハイオ州立大学だった。そこで渡米しストリキニーネの合成などの研究成果を上げると、今度はシカゴ大学からオファーが来た。アメリカの懐の深さと、研究者ネットワークの強さを感じた瞬間だった。

その恩返しとして、現在、岩佐教授は留学生の受け入れを積極的に行う。研究室には、中国やモンゴル、ラオス、マレーシアなど、8カ国もの学生が在籍しているという。

「そうやって世界を知ることで、日本の良さを再認識できる。技術力の高さやモラリティの高さ、環境への配慮など、日本の良さをぜひ、世界に広めていきたい。そのために、現在、アジアでの日本語教育にも注力しているところです」と岩佐教授。

その好奇心は、研究だけでなく教育や環境にも広がっている。

Researcher Profile

Dr. Seiji Iwasareceived Ph.D. degree in Engineering from Chiba University in 1991. After getting his Ph.D., he was engaged in research as Post Doctoral Research Associates in Ohio State University, University of Chicago, and ERATO respectively. Currently, Dr. Iwasa is a professor in Department of Environmental and Life Sciences at Toyohashi University of Technology. His research interests are asymmetric synthesis, carbene, diazo compound, natural product, and so on.

Reporter Profile

Madoka Tainaka is a freelance editor, writer and interpreter. She graduated in Law from Chuo University, Japan. She served as a chief editor of “Nature Interface” magazine, a committee for the promotion of Information and Science Technology at MEXT (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology).

ここでコンテンツ終わりです。