ここからコンテンツです。

Revealing Internal Changes in Metallic Materials in Three Dimensions Using Synchrotron Radiation

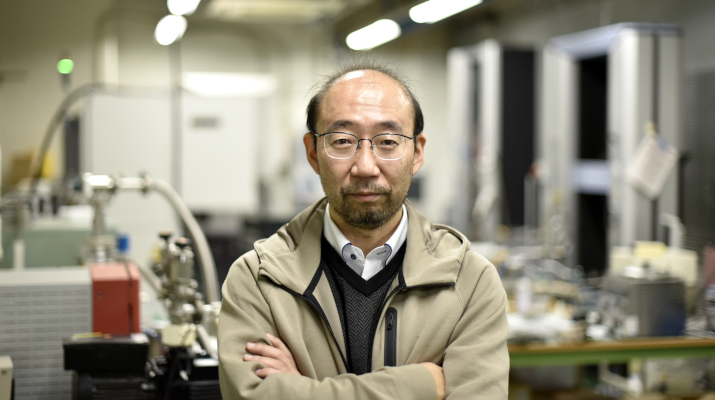

Masakazu Kobayashi

Metallic materials such as steel and aluminum, which are indispensable for many industrial products, experience complex internal deformations that cannot be observed when external forces are applied. Yet the mechanisms behind these internal changes are still not completely understood. Professor Masakazu Kobayashi is working to clarify these mechanisms using SPring-8 and other large synchrotron radiation facilities to produce three dimensional visualizations of microscopic deformations inside metallic materials.

Interview and report by Madoka Tainaka

Observing Changes Occurring Inside Metals

Metals consist of collections of tiny crystals, or grains, that measure up to several tens to several hundreds of micrometers. A defining feature of these metallic crystals is their capacity to undergo plastic deformation when subjected to external forces. When a force is applied, linear crystal defects known as dislocations frequently form within the grains, shifting regularly arranged atoms and generating deformation. This property enables metals to be shaped into many forms; therefore, they have been used across numerous industrial fields.

“However, we still lack a full understanding of where slip is concentrated and how internal changes unfold on a microscopic scale. Plastic deformation can certainly be mathematically expressed using a crystal plasticity model and can be simulated to some extent. But I question whether these simulations truly reflect reality. My motivation is to directly observe what is happening inside metals,” explains Professor Masakazu Kobayashi.

To date, practical experience in metal processing has indicated the existence of regions in which deformation tends to concentrate, and efforts have been made to locate these regions and create high strength materials. Obtaining the ability to predict such locations in advance could guide the development of even stronger materials in the future.

“When metal is repeatedly bent and stretched, it becomes harder and eventually fractures, but heating softens it again. During this process, atoms slide internally, forming crystal defects that alter the metal’s properties and increase its hardness, but heat application results in recrystallization and grain growth, causing the crystals to enlarge. However, these changes do not progress evenly across the metal, with some areas undergoing intense deformation and others not. Why does this happen? I would like to identify the regions where deformation preferentially takes place and investigate the reasons behind it.”

Approaching Microscopic Internal Changes in Metals at SPring-8

Conventional observation techniques such as electron microscopy have facilitated only surface level inspection of metals. Professor Kobayashi believes that metals are constrained by neighboring crystals; thus, internal changes in the metal do not necessarily match what appears on the surface.

“Observing a metal’s interior in three dimensions without destroying it requires X rays of extremely high intensity, far exceeding the levels used in medical CT. Therefore, beginning around 2004, we started conducting experiments at SPring-8, the world’s highest performing synchrotron radiation facility in Hyogo Prefecture. In these experiments, we examine changes that occur while pulling square bars of aluminum alloy roughly 500 to 600 µm thick.”

Aluminum alloys are selected because they are widely used, possess a relatively simple crystal structure (a face centered cubic (FCC) lattice) with slip as the primary deformation mechanism, and have a low melting point that permits many alloy variations to be fabricated in the laboratory. Another aim is to clarify the differences in deformation mechanisms among materials by modifying the alloying elements.

However, only a few methods are capable of nondestructively observing the interiors of metals in three dimensions.

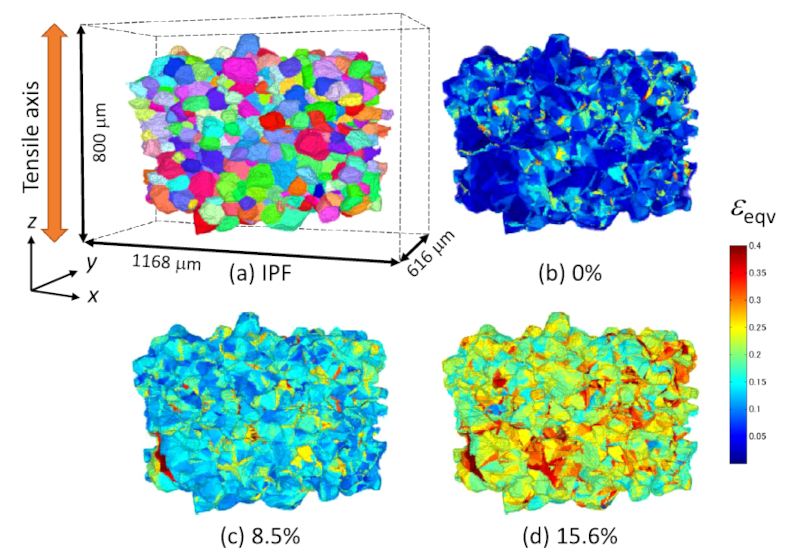

“Understanding deformation in detail requires markers that indicate the location and magnitude of movement. We therefore developed a technique that tracks the amount of movement by adding lead particles to aluminum or by using the numerous micropores (voids) inside the material as markers. The sample undergoes repeated processes of slight stretching and imaging, which allows us to obtain three dimensional data describing the crystal orientation in each region, slip deformation directions, deformation concentration zones, and strain changes over time, which we then convert into images through computer analysis.”

These experimental techniques were created through many years of joint research with the Technical University of Denmark. Professor Kobayashi spent roughly a year conducting research at the Technical University of Denmark about 10 years ago through the university’s overseas training program, and has continued the collaboration to the present day, steadily refining his observational methods.

“The group involved in this research later launched a venture company and produced a commercial measurement instrument. Our laboratory is now collaborating with this company while conducting research using SPring-8.”

Discovery that Initially Deformed Regions Continue to Deform

What have the researchers begun to learn from the three dimensional data obtained in these observations? Professor Kobayashi carefully chooses his words as follows:

“It had been commonly assumed that once a region deformed, it hardened and became less likely to deform, and that other regions would then deform instead. However, our observations revealed that the region that deformed first continued to deform afterward. Conversely, the areas that had not deformed remained unchanged indefinitely. In short, metals contain regions that continue to move and others that barely move at all. These differences are thought to arise from specific interactions between adjacent crystal grains, influenced by factors such as grain shape and orientation. These findings will help advance our understanding of the mechanism of complex plastic deformation of crystal grains inside metals. If conventional simulations cannot reproduce this behavior, the simulation methods themselves will also need revision.”

If interactions between grains that initiate deformation can be clarified and the regions that continue to deform can be identified, it may become possible to design metals with greater resistance to fracture.

Professor Kobayashi emphasizes fundamental research to uncover underlying principles, but he is also engaged in collaborative projects with automotive parts manufacturers and others.

“With the rise of electric vehicles, companies that once specialized in producing automobile engines are seeking new fields. One promising area is manufacturing body components made from cast aluminum. In this process, recycled aluminum must be used for carbon neutrality, but recycled materials are more susceptible to impurities that can reduce toughness, raising concerns about ensuring safety in collisions. We are therefore studying why impurities make materials more brittle and to what extent such impurities are acceptable. This research is possible only because we possess the rare capability to observe crystal deformation directly.”

Another advantage of the Kobayashi Laboratory is its strong connection to SPring-8. Although the facility is open to researchers from Japan and overseas, many companies hesitate to use it because of the advanced expertise required and the need to apply in advance.

“I have used this beamline for over 20 years and know the staff well, so if any company wishes to use it, we can help connect them with the appropriate personnel.

I believe future materials research will focus not only on durability but also on recyclability and controlling how materials fail. Achieving this requires a thorough understanding of deformation and fracture mechanisms. Materials research in metals is one of Japan’s strengths, and I hope to continue contributing to its progress,” says Professor Kobayashi. Further exploration of these fundamental principles is eagerly anticipated.

Reporter's Note

Professor Kobayashi has been fascinated by machines since childhood and studied mechanical engineering in university with the idea that he might eventually work in the automotive sector. “I discovered the compelling intersection of physics and chemistry found in metallic materials research while studying crystal growth simulations in graduate school,” he recalls. This period also coincided with advances in two dimensional crystal orientation measurement tools and computer-based image analysis using digital data. “My enduring interest has been in uncovering what cannot be seen,” he says. This curiosity aligns with one of humanity’s deepest fascinations. We look forward to seeing what future research reveals about the unseen worlds that lie inside metals.

放射光で金属材料の内部変化を3次元で解き明かす

小林正和鉄やアルミなど、さまざまな工業製品に欠かせない金属材料は、外部から力が加わることで、その内部では目に見えないレベルで複雑な変形が生じている。だが現状、そうした変化がどのように起こっているのか、完全には解き明かされてない。小林正和教授は、大型放射光施設「SPring-8」などを利用して、金属材料内部の微細な変形を3次元で可視化しながら、そのメカニズムの解明に挑んでいる。

金属の「内部」で起きている変化を見たい

金属はおよそ数十〜数百μmの微細な結晶(結晶粒)の集合体で構成されている。その金属結晶の主な特徴は、外部から力を加えると塑性変形すること。力が加わると、多くの場合、「転位」と呼ばれる線状の結晶欠陥が結晶粒内に生じて、規則的に並んだ原子をずらし、変形することがわかっている。この性質を利用して自在な形に加工できることから、金属は古くから工業製品の材料としてさまざまに活用されてきた。

「しかし本当のところはどのようなところで滑りが集中的に起こっているのか、ミクロなレベルでの内部変化の詳細は、いまだによくわかっていないのです。もちろん、塑性変形については結晶塑性モデルによって定式化されており、シミュレーションによって、ある程度は再現できます。でも、それが本当に事実と合っているのかどうか。金属内部の変化を直接観察してみたいというのが私の研究のモチベーションになっています」と小林正和教授は語る。

これまで金属加工の現場では、経験上、変形が集中する箇所が存在することが知られており、その箇所を見分けながら、強度の高い材料を生み出す工夫がなされてきた。それがどういった場所で起こるのかを予測できれば、将来的にはより強靭な材料開発に役立つ可能性がある。

「金属の曲げ伸ばしを繰り返すと硬くなって、やがて壊れてしまいますが、熱を加えるとまた柔らかくなりますよね。このとき、内部では原子が滑って結晶欠陥ができ、それにより性質が変わって硬くなるけれど、熱が加わることで再結晶化して、さらに粒成長が起きて結晶が大きくなる、という現象が起きています。しかしそうした変化は金属全体に均一に起こるわけではなく、場所によって激しく変形が起こるところと、そうでないところがあるのです。それはなぜなのか。優先的に変形が起こる場所を突き詰め、その原因を探りたいと思っています」

「SPring−8」で金属内部の微細な変化に迫る

しかしながら従来、電子顕微鏡などによる観察方法では、金属の表面上の変化しか見ることができなかった。金属内部では隣り合う結晶に拘束されることから、表面と同じような変化が起きているとは限らない、と小林教授は考えてきたという。

「金属内部を3次元で非破壊的に観察するためには、医療用のCTよりも超高輝度のX線が必要なります。そこでわれわれは、2004年頃から兵庫県にある世界最高性能の大型放射光施設SPring-8で実験を重ねてきました。500〜600μmほどのアルミ合金の角棒を引っ張りながらその変化を調べるのです」

なお、アルミ合金を使うのは、一般的によく使用される金属であることに加えて、結晶構造が面心立方格子(FCC)型で変形機構が滑りに限定されるなど比較的単純であること、融点が低く実験室でさまざまな合金をつくることが可能であることなどによる。添加する元素を変えることで、物質ごとの変形メカニズムの違いを明らかにする狙いもある。

一方、現状は金属内部を非破壊で、しかも3次元で見る手法は限られている。

「変形の詳細を見るためには、どこがどう動いたのかを知るためのマーカーが必要です。そのため、われわれはアルミに鉛粒子などを添加してマーカーにしたり、内部に無数にあるミクロのポア(空隙)をマーカーにしたりして、その移動量を追跡する手法を開発してきました。そして試料を少し引っ張っては撮影し、また引っ張っては撮影するということを地道にくり返しながら、局所ごとの結晶の向きや滑り変形の方向、変形が集中する箇所、ひずみ量の時間的変化などを3次元データとして取得し、コンピュータ解析により画像にして可視化しているのです」

実は、これらの実験手法は、小林教授が長年にわたりデンマーク工科大学との共同研究を通して培ってきたものだ。10年ほど前に大学の海外研修員制度を活用して1年間ほどデンマーク工科大学で研究活動を行ったのを機に、現在まで共同研究を続け、観察手法に磨きをかけてきたという。

「当時、その技術を研究していたグループが後にベンチャー企業を立ち上げ、市販装置として計測装置をつくったのです。現在、われわれの研究室でもその企業の協力を得て、SPring-8と組み合わせながら研究を進めています」

最初に変形したところが変形し続けるという発見

では観察で得られた3次元データから何がわかりつつあるのか。小林教授は慎重に言葉を選びながらも、次のように語る。

「これまで一般的に、一度変形した部分は硬くなって変形しづらくなり、別の箇所が変形すると考えられていたんですね。ところが、われわれの観察から、最初に変形した領域がその後も継続して変形し続けることが確認されました。しかも、変形しないところはずっとそのまま残り続ける。つまり、金属内部では動き続ける領域と、ほとんど動かない領域があるということ。これは、結晶粒の形状や配向の違いなど、隣接する結晶粒間の特定の相互作用に起因するものと推測されます。この観察結果は、金属内部の結晶粒の複雑な塑性変形メカニズム解明の一つの布石になるだろう、と。そしてもし、これが従来のシミュレーション予測で再現されないのであれば、シミュレーションの手法も更新する必要があると考えています」

変形のトリガーとなる結晶粒間の相互作用を明らかにし、変形し続ける箇所を特定できれば、将来的には、壊れ難い金属材料を設計することができるかもしれない。

また、小林教授は原理の解明という基礎研究に重きを置きつつも、自動車の部品メーカーなどとの共同研究も進めている。

「これまで車のエンジンを製造してきたメーカーが、昨今のEV化の流れで、新たな事業領域を模索しているのです。その一つが、アルミニウム鋳造によるボディ部品の開発です。その際、カーボンニュートラルの観点から、リサイクルアルミの活用が求められていますが、再生材は不純物が混入しやすく、靱性(ねばり)が低下する恐れがあり、衝突の際の安全性をどう担保するのかが課題となっているのです。そうしたなかで、不純物があるとなぜ壊れやすくなるのか、不純物がどれくらいまでなら許容できるのかといったことを調べています。これはまさに、われわれが結晶の変形を見るという希少な技術を携えていればこそできる研究と言えます」

さらに小林研究室の強みが、SPring-8に通じている点だ。この施設は国内外の研究者に広く開かれた共同利用施設ではあるが、高度な専門知識が必要なことや、利用のための事前申請などのプロセスを経る必要があるため、敷居が高いと感じる企業は少なくない。

「私自身はすでに20年以上利用させてもらっていて、ビームラインの担当者とも顔馴染みですので、使ってみたいという企業があれば、ご相談いただければ橋渡し的な役割を担えると思います。

これからの材料研究は、単に壊れにくいというよりも、リサイクルのしやすさや壊れ方の制御がポイントになると思います。その実現のためには、変形や破壊のメカニズムを正しく理解する必要がある。金属材料研究は日本の強みでもありますので、その発展にこれからも貢献していきたいと思います」と小林教授。今後のさらなる原理の究明に期待したい。

(取材・文=田井中麻都佳)

取材後記

幼い頃から機械が好きで、大学では機械工学部へ進学し、将来は自動車業界にでも就職するかな、と思っていたという小林教授。「大学院で結晶成長のシミュレーションの研究をするなかで、物理と化学が交差する金属材料研究の面白さに目覚めました」と語る。ちょうど、2次元で結晶の向きを調べる装置や、デジタルデータを使ってコンピュータで画像解析する技術が進展していくタイミングでもあった。「結局、見えないものを見てみたい、というのが一貫した興味なんですね」と小林教授。まさにそれこそが人類最大の興味と言える。まだ見ぬ金属の内部にどんな世界が広がっているのか、今後のご研究を楽しみにしています。

Researcher Profile

| Name | Masakazu Kobayashi |

|---|---|

| Affiliation | Department of Mechanical Engineering |

| Title | Professor |

| Fields of Research | Analysis and evaluation of material microstructure / X-ray imaging |

Reporter Profile

Madoka Tainaka

Editor and writer. Former committee member on the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Council for Science and Technology, Information Science Technology Committee and editor at NII Today, a publication from the National Institute of Informatics. She interviews researchers at universities and businesses, produces content for executives, and also plans, edits, and writes books.