ここからコンテンツです。

Using Computational Models to Elucidate the Mechanism of the Human Auditory System

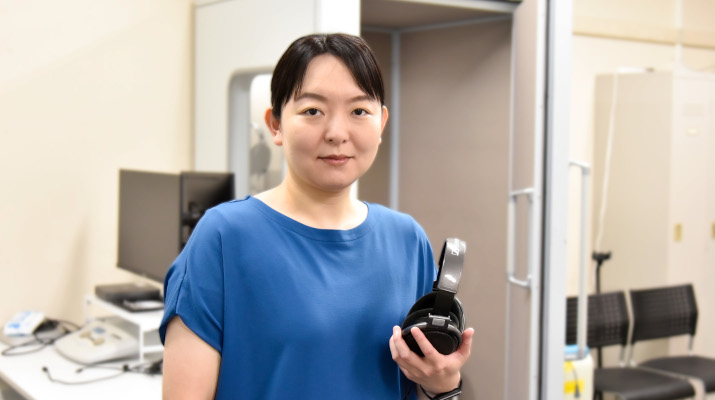

Toshie Matsui

Professor Toshie Matsui is working to elucidate the mechanism of the human auditory system, which has not yet been fully understood due to its complexity. To achieve this, she uses computational models that represent processing in the auditory pathway, as well as a simulated hearing impairment system that reproduces the hearing of individuals with hearing loss. By conducting psychophysical experiments using these methods and repeatedly verifying the results, she aims to deepen the understanding of the auditory mechanism and to better untangle the puzzle of what creates “ease of hearing.”

Interview and text by Madoka Tainaka

The auditory system: complex and largely unexplained

When people think of auditory research, they usually tend to think of the ears. However, just as how vision is about more than the eyes, “hearing” involves more than the ears alone. Sound entering the ear causes the eardrum to vibrate, and this vibration travels through the cochlea, a snail-shaped organ in the inner ear, where it is converted into neural signals by the auditory nerve. These signals then travel through the brainstem and thalamus before reaching the auditory cortex in the cerebral cortex. This pathway is exceedingly complex. Therefore, as Professor Matsui explains, many aspects of auditory function remain unexplained.

“The auditory pathway from the ear to the auditory cortex travels from the peripheral system, including the ear and cochlea, to deep parts of the brain, such as the brainstem, making it difficult to observe. Moreover, there are many neural nuclei that relay neural signals, resulting in a very complex pathway. So, how can we investigate it? One method is to use computational models and simulations. Various researchers have already developed auditory models, and by utilizing these, I am attempting to elucidate parts of the complex auditory mechanism through psychophysical experiments that verify their accuracy.”

Using a simulated hearing impairment system to replicate the actual hearing experience of the elderly

One of the methods used by Professor Matsui is the Wadai Hearing Impairment Simulator, which was developed by Professor Toshio Irino and his team at Wakayama University. This system can replicate the auditory experience of individuals with hearing impairments, making it a valuable tool for understanding the difficulties associated with hearing loss and the experience of those with it.

“It is often said that, as people get older, their hearing declines. Using this simulated hearing impairment system, we can verify exactly what parts of the hearing process deteriorate and how it affects their hearing. Additionally, we intend to determine whether this system truly corresponds to the real hearing experiences of the elderly. If it does not, we want to identify the causes and use that information to make improvements,” says Professor Matsui.

The simulated hearing impairment system is an excellent tool that allows us, simply by inputting the results of a subject's audiogram, to simulate the processing in their peripheral auditory system and reproduce the sounds heard by the individual. However, because the simulation is inherently an approximation, its reproducibility can vary depending on the environment and conditions. Professor Matsui is investigating under what circumstances the system may not accurately reproduce hearing.

“For example, we conducted an experiment involving both young individuals with normal hearing and elderly participants. The young participants were not only involved in regular auditory perception experiments, but also listened to sounds processed by the simulated hearing impairment system, effectively participating in this case as ‘simulated elderly individuals.’ As a result, it was found that the simulated hearing impairment system could relatively accurately reproduce the hearing of elderly individuals with good hearing, but its reproducibility was lower for those with poor hearing. Additionally, reproducing hearing in environments with irregular noise, such as background chatter, proved challenging. In other words, simulations limited to the peripheral system alone may not sufficiently explain the state of hearing.”

It has long been known that elderly individuals have difficulty hearing consonants. They also struggle to catch notification sounds from household appliances such as chimes or spoken messages. Using the simulated hearing impairment system, Professor Matsui and her team confirmed that elderly individuals (or those with simulated elderly hearing) also have difficulty detecting the engine sound of approaching cars. As the number of people with age-related hearing loss is expected to continue increasing, designing sound environments that facilitate easy hearing will become extremely important. In this respect, being able to clarify the specific “hearing” characteristics of elderly individuals will be very valuable.

“Hearing loss is considered a risk factor for many diseases, including dementia. Additionally, as hearing loss progresses, it becomes difficult to communicate with others, which can hinder social life. Moving forward, we aim to use this simulated hearing impairment system to clarify what kind of clear speech makes it easy for everyone to hear. We also hope to contribute to the education of speech-language-hearing therapists and the improvement of hearing aids.”

Understanding the auditory mechanism through reactions to and perceptions of sound

Another area of focus for Professor Matsui is the field of “auditory feedback in vocalization.” This refers to the function by which humans hear their own voice and adjust their speech accordingly. Although this function itself has long been understood, Professor Matsui and her team are now investigating auditory feedback using sounds produced from artificial stimuli.

“For example, we are currently conducting experiments as a part of a joint research project with Prof. Hideki Kawahara, Professor Emeritus of Wakayama University. In these experiments, we introduce slight tremors or irregular changes in the pitch and duration of the stimulus sound, and observe how these variations affect human vocalization when participants adjust their voices to match the pitch.”

Professor Matsui and her team focus on a rapid response known as the “involuntary response.” Previous research has shown that there are two types of vocal responses to sounds which include fluctuations and last for 500 ms or longer, which are differentiated by the latency period from stimulus onset to response. The slower response varies depending on experimental conditions, whereas the faster response shifts the vocal pitch in the opposite direction of the stimulus pitch variation, compensating for it. Due to its short latency, this fast response is considered involuntary. Based on this knowledge, Professor Matsui and her team are conducting experiments to investigate the characteristics of auditory feedback in greater detail by varying the types and magnitudes of stimulus sounds.

“The sounds we typically hear consist of a fundamental frequency, which is the base frequency, with harmonic overtones that are integer multiples of that frequency, creating complex sounds. In contrast, a sound that contains only a single frequency component is called a pure tone, and a sound with only higher harmonics, excluding the fundamental frequency, is known as a missing fundamental. We investigated involuntary responses by having participants listen to these various sounds and vocalize in response to them. The results showed that pure tones failed to elicit any responses, while harmonic complex sounds containing higher harmonics but lacking fundamental frequency drew only limited responses. This indicates that the responses to instantaneous fundamental frequency variations are likely influenced by the lower harmonics.”

What are Professor Matsui and her team trying to uncover through this research? She explains, “If we can identify the indicators necessary to control the relationship between hearing and vocalization, we may be able to gain clues about the pathways and processes occurring in the brain.” In other words, they are seeking to gain insights that could help elucidate the fundamental mechanisms of the still largely unexplained auditory system.

Additionally, they are conducting experiments to look at how humans distinguish between male and female voices, differentiate between various speakers, and perceive non-verbal information, such as distinguishing angry voices from neutral ones.

“Furthermore, in our laboratory, we also focus on music. For example, one of our students set up a program that can generate melodies and found that songs with more syncopation tended to sound better, even if the melodic contour is unchanged. Personally, having played the piano since childhood, I have always wondered why listening to music can be so fun, and spark various emotions within us. I also want to explore the characteristics of trained musicians who have accumulated years of practice. My ultimate dream” concluded Professor Matsui, “is to be able to explain music in terms of logic,”.

Reporter's Note

Starting piano lessons in kindergarten, Professor Matsui went on to attend Nishinomiya High School in Hyogo Prefecture, which is renowned for its music program, , before enrolling at Kyoto City University of Arts. During her graduate studies, she spent a year studying piano in the United States before returning to Japan to complete a master’s degree in instrumental performance.

“To earn a master’s degree in performance, I had to give an 80-minute solo recital as well as writing my thesis. The thesis I wrote on music psychology back then has led me to where I am today,” Professor Matsui explains. Although, Professor Matsui chose to concentrate on research rather than performance after graduating. It is her unique combination of research with her experience and perspective as a performer that makes us particularly anticipate her future work .

計算モデルを用いて、聴覚メカニズムを解き明かす

松井 淑恵松井淑恵教授は、その複雑さゆえに、いまだ十分に解明されていない人間の聴覚メカニズムの解明に取り組んでいる。そのために用いるのが、聴覚経路における処理を表現した計算モデルや、難聴者の聞こえを再現した模擬難聴システムなどだ。これらの手法を用いた心理物理学的実験により検証を重ねながら、聴覚メカニズムへの理解を深めることにより、「聞こえやすさ」の手掛かりを探ろうとしている。

複雑で未解明な部分の多い聴覚

聴覚の研究というと、多くの人は耳を思い浮かべるだろう。しかし、視覚などと同様に、「聞こえ」は耳だけの問題ではない。耳に入った音は鼓膜を振るわせ、内耳にあるカタツムリのような形をした蝸牛(かぎゅう)という器官を経て、聴神経の発火(信号)へ変換されて、脳幹、視床を経て大脳皮質の聴覚野に至るという、非常に複雑な経路を辿る。ゆえに、聴覚機能にはいまだ解明されていない部分がたくさん残っているのだと、松井教授は語る。

「耳から聴覚野に至る聴覚経路というのは、耳から蝸牛までの末梢系を経て、脳幹などの脳の奥深くへ伝わっていくため観察しにくいうえ、神経信号の中継となる神経核が多く経路がとても複雑なのです。ではどうやって調べるのか。一つには、コンピュータによる計算モデルやシミュレーションを活用する方法があります。すでに様々な研究者が聴覚モデルを開発していて、私はこれらを活用しながら、心理物理学的な実験により、その正しさの検証などを通じて、複雑な聴覚メカニズムの一端を解明しようとしています」

「模擬難聴システム」を活用して、高齢者のリアルな聞こえに迫る

その手法の一つとして松井教授が用いるのが、和歌山大学の入野俊夫教授らが開発した「模擬難聴システム:Wadai Hearing Impairment Simulator, WHIS」だ。これは、難聴者の「聞こえ」を再現できるもので、聞こえにくさの体験・理解に役立つシステムである。

「お年寄りになると耳が遠くなるとよく言われますが、どこがどう悪くなって聞こえづらくなるのか、実際にどのように聞こえているのかを、この模擬難聴を使って確かめることができます。一方で、これが本当にお年寄りのリアルな聞こえに対応しているのかどうか、もし対応していないとしたらどこに原因があるのかを探り、その改善に役立てようとしているのです」と松井教授は言う。

模擬難聴システムは、対象者の聴力検査の結果を入力すると、聴覚末梢系の機能における処理を模擬し、対象者が聴取する音を再現できる優れたシステムだ。ただし、シミュレーションはあくまでも模擬的なものなので、環境や条件によって再現性が異なる。どのような場合に、うまく再現できないのかを松井教授は探っているという。

「例えば、若い健聴者と高齢者に参加していただいた実験があります。若い健聴者には、通常の音声聴取実験だけでなく、模擬難聴で処理した音を聞いてもらい、『模擬高齢者』としても実験に参加してもらいました。その結果、この模擬難聴システムが、耳のいい高齢者については比較的うまく再現できるのに対して、耳の悪い高齢者については再現性が低いことがわかりました。また、ザワザワとした非定型なノイズがある環境下での聞こえの再現も難しい。つまり、末梢系だけのシミュレーションでは、聞こえの状態を十分には説明できないと言えます」

以前から、高齢者は家電のピーピーというお知らせ音や子音が聞こえづらいことが知られていたが、松井教授らは、この模擬難聴システムを活用して高齢者(模擬高齢者)が車のモーター音の接近に気づきにくいことを確かめた。今後、老人性難聴者が増え続けていくことが予想されるなか、聞きやすい音環境のデザインは極めて重要になる。そのときに、高齢者がどういった「聞こえ」の特性を有するのかを明らかにすることは、非常に有用だろう。

「難聴は認知症をはじめ、多くの病気のリスク要因であるとされています。また、難聴が進むと他者とのコミュニケーションが困難になって、社会生活に支障をきたします。今後は、この模擬難聴システムを使って誰もが聞きやすい明瞭な音声を明らかにするとともに、言語聴覚士の教育や補聴器の改善などにも役立てられたらと考えています」

音に対する反応や感じ方を通じて、聴覚メカニズムの解明へ

もう一つ、松井教授が注力するのが、「発声における聴覚フィードバック」の分野だ。これは、人間が自分の発した声を自分で聞くことで発声を調整する機能のこと。この機能自体は古くから知られているが、松井教授らは人工的な刺激音による聴覚フィードバックについて調べている。

「例えば、刺激音を微小に震わせたり、不規則に音の高さや長さを変えたりしながら、その高さに合わせて発声してもらったときに、人間の発声にどのような変化が見られるかを実験しています。こちらは、和歌山大学名誉教授の河原英紀先生らとの共同研究になります」

このなかで松井教授らが注目するのが、「不随意応答」と呼ばれる、速い反応だ。先行研究により、500 ms以上持続する音の変動に対して、刺激が与えられてから反応が起こるまでの間(潜時)が異なる、2種類の発声応答があることがわかっている。遅い応答は実験条件によって異なる応答を見せるが、速い応答は刺激のピッチ変動とは逆の方向、つまり刺激のピッチ変動を補償する方向へ発声ピッチがシフトする。この速い応答はその潜時の短さから、自発的にコントロールのできない、不随意なものであると考えられている。松井教授らは、この知見をベースに刺激音の種類や変化量を変えながら実験を行うことで、聴覚フィードバックの特性を詳しく調べている。

「私たちが普段耳にする音というのは、基底となる基本周波数(ファンダメンタル)があって、その上にその周波数の2倍、3倍といった、整数倍の倍音が重なる複合音です。一方、一つの周波数成分しか含まない音は純音、また、基本周波数を含まない高次の高調波のみの音は、ミッシングファンダメンタルと呼ばれます。こうした様々な音を聞いて、それに合わせて発声してもらうことで、不随意応答を調べました。その結果、純音では応答が見られないことや、(基本周波数を含まない)高次の高調波のみのミッシングファンダメンタル音では、応答が小さいことなどがわかりました。つまり、瞬間的な基本周波数の変動に対する応答には、低次の高調波が影響しているだろうということがわかったのです」

このような研究を通じて、何を解き明かそうとしているのか。松井教授は、「聴覚と発声の関係をコントロールするのに必要な指標がわかれば、脳内でどのような経路で、どのような処理が行われているのか、その手がかりが得られるかもしれない」と語る。つまり、未解明な聴覚の根本的なメカニズムを解明するための手がかかりを得ようとしているのだ。

さらに、人間は男性と女性や、異なる話者をどう聞き分けているのか、怒っている音声とニュートラルな音声をどう聞き分けているといった、非言語情報に対する知覚についても実験を重ねている。

「そのほか、うちの研究室では音楽も対象にしています。例えば、自分でメロディを生成できるプログラムを組んで、同じメロディであっても、シンコペーションを多用するほどいい感じの曲になるということを確かめた学生もいました。私自身、幼い頃からピアノを演奏してきたこともあって、音楽を聞いて様々な情動を感じ、楽しめるのはなぜか、といった疑問や、長年訓練を積んできた演奏家の特性などについても、追究していきたい。最終的な夢は音楽を理屈で語れるようになることです」と松井教授は締めくくった。

(取材・文=田井中麻都佳)

取材後記

幼稚園のときからピアノを習い、音楽科があることで有名な兵庫県立西宮高校を経て、京都市立芸術大学へ。大学院に在籍中にピアノで米国に1年間留学した後、帰国後は器楽専攻で修士課程を修了した。「演奏で修士を取るためには80分のソロリサイタルを開くことに加え、論文を書く必要が当時はありました。そのとき書いた音楽心理学の論文がいまにつながっています」と松井教授。博士課程からは、演奏でなく研究の道へ。演奏家としての経験と視点を生かした独自の音楽研究に、大いに期待しています。

Researcher Profile

Toshie Matsui

Toshie Matsui received PhD degree in 2010 from Kyoto City University of Arts, Kyoto, Japan. After a postdoctoral research fellowship at Kwansei Gakuin University, Nara Medical University, and University of Tsukuba, and an assistant professor at Wakayama University, she started her career as an associate professor at Toyohashi University of Technology in 2017. She is currently a professor at Institute for Research on Next-generation Semiconductor and Sensing Science (IRES2).

Reporter Profile

Madoka Tainaka

Editor and writer. Former committee member on the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Council for Science and Technology, Information Science Technology Committee and editor at NII Today, a publication from the National Institute of Informatics. She interviews researchers at universities and businesses, produces content for executives, and also plans, edits, and writes books.