ここからコンテンツです。

Machine Translation Opening Japan to the World

Hitoshi Isahara

Machine translation technology is making progress every year, and against the backdrop of big data technology development, hopes are high for achieving ever greater accuracy. However, while machine translation among Western languages is approaching the level of practical use, there are still many hurdles which hamper machine translation from Japanese to other languages. We talked about this topic with Professor Hitoshi Isahara, who has been tackling these issues in his work at the cutting edge of machine translation research since the 1980s.

Interview and report by Madoka Tainaka

Obstacles to Effective Japanese Machine Translation

Professor Hitoshi Isahara came to Toyohashi University of Technology in 2010 to further his pursuit of machine translation research. This research was a continuation of his work with the Ministry of International Trade and Industry’s (MITI) Electrotechnical Laboratory, and the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications’ Communications’ Research Laboratory (currently the National Institute of Information and Communications Technology, NICT).

“I have worked on a variety of research projects, such as machine translation of Japanese into Chinese, Thai, Malay, and Indonesian, the creation of a database of spoken Japanese and the development of Japanese-Chinese and Chinese-Japanese language processing technology, etc. However, unfortunately, while the accuracy of machine translation from Japanese into those other languages is improving, it is still inadequate. For example, when translating from Japanese to English, in addition to the differences in word order, Japanese has the peculiarity of context dependence. For example, Japanese often omits subjects, and this becomes an obstacle for translation. In order to use the machine translation for information outbound transmission, the quality needs to be fully guaranteed, but in reality the output of machine translation systems can not yet be relied upon. In order to make the output useful, we need to employ all kinds of ingenuity,” says Professor Isahara.

In fact, in the 1980s, Japan was the world leader on machine translation research. In addition to academic research by universities, many major electronics companies also invested in machine translation system development. Before long however, business interest in the field petered out. Professor Isahara says that the reason behind this they lacked the concept of providing a “service” to users. Companies simply applied the existing business model of creating, packaging and selling a system to the process of commercialization of machine translation technology, but this model produced unsatisfactory results for users.

“In addition one must consider the fact that in Japan there was little concept of systematically documenting and recycling information, so there was no structure in place for incremental system development and the provision of continuous service. Even for professional translators, knowledge of the domain and prior detailed information are essential. Likewise, for machine translation, the construction of a frequently updated user friendly database as well as development of operating techniques and mechanisms are just as indispensable as improvements in the accuracy of the translating engine.”

The three essential steps for machine translation

In this context, Professor Isahara cites the following three elements are essential to the process used in machine translation: (1) create Japanese text that is easy to translate by machine, (2) extract salient terms that fit with the field, and (3) build a post-editing environment.

“First of all, just following Step 1, making the Japanese input easy to translate, is quite effective. I then researched what kind of input sentences would make the machine translation go smoothly, without lowering the quality of the Japanese.”

To test this, he asked for cooperation from a local business, getting them to rewrite their company manual based on his rules for easy-to-translate Japanese, so-called “controlled language,” and conducted an experiment to measure the accuracy of the translation. The rules were simple: to include subjects and objects wherever possible, to avoid long sentences, and to avoid complex expressions. In the context of such research developments, and given the essential role of controlled language, the International Organization for Standardization is currently promoting international standardization in this field.

Step 2, the extraction of terms, means accumulating a large volume of documents related to a particular field, and from that list, semi-automatically extracting often-used “moderately long phrases”. “For example, these are phrases such as ‘the effect of carbon dioxide on global warming’ or ‘gas decompression characteristics when fissures occur in the pipeline’. These are automatically extracted and carefully examined by those well versed in the field. Appropriate parallel translation glossaries are prepared in advance.”

The final step is Step 3, post-editing. For this, Professor Isahara has incorporated the use of social crowdsourcing. Currently the task of post-editing cannot be omitted, since the quality of the document will suffer without adjusting the translated text. However, relying on professional translators is very costly. Therefore, as a cost effective solution, he recruits volunteers with suitable knowledge in the field assist with the work. The Toyohashi University of Technology website (English version) has been equipped with a machine translation engine and editing tools, and he found that with the help of foreign students in post-editing, it is possible to get an accurate translation.

“Our foreign students know a lot about the university, and so well able to manage quality control. For example, several students collaborated to correct a text translated from English into Indonesian, with the result that they were able to achieve a level of accuracy close to that of a professional translator.”

Involving social communities of various fields

Presently, in the business world, translation is generally left up to professional translators from the get-go, but the merit to bringing in machine translation is that even if the accuracy is modest, you can speed up the process without incurring any costs. In the current context of trends such as globalization and an influx of foreigners to Japan, as well as a revitalized inbound market, the demand for outbound information through machine translation will surely continue to rise.

“For example, Japan is getting ready to host the Rugby World Cup in 2019, and from now, there will certainly be more and more articles posted in Japanese. When that happens, if we can get help with post-editing by rugby fans, we anticipate that we will be able to transmit information fairly well in English. By gathering and studying the results of those translations, we will also be able to further improve translation accuracy. In particular, I would be so happy if senior citizens who have a lot of knowledge and ability and want to contribute to society, would participate in social crowdsourcing. Although it is basically volunteer work, we might need to prepare some incentives, such as giving autographs of famous players for each contribution,” says Professor Isahara. In fact, a joint research project on the topic of translating rugby articles, has already been commenced by Toyohashi University of Technology in collaboration with Rikkyo University and NICT.

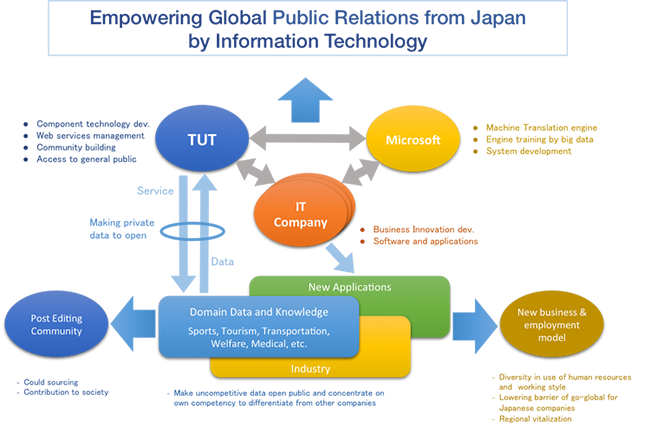

In the future, Professor Isahara says that he would like to facilitate better public relations in English between Japan and the world through volunteer networks in various fields of interest to foreigners, such as railways cameras and ramen. Furthermore, he is concentrating on developing links with IT companies to create shared databases for manuals for business use, and other purposes. He has already launched such a joint project with Microsoft Japan and BroadBand Tower, Inc. Regarding future prospects, Professor Isahara says that the translation of various languages will expand from the base of Japanese-English translation, which may eventually result in the creation of a new international community. Although the issue of quality assurance remains a challenge, Professor Isahara will continue to strive to make machine translation more useful to society.

Reporter's Note

Professor Isahara, having initially worked on natural language processing, eventually switched to translation engine research and has been devoting his energies to this field ever since. He is currently shifting the basis of his research to more directly practical applications, through the extraction of terms and the creation of a framework that aims for practical use.

“I have been engaged in Japanese machine translation since the early days, and I am still continually searching for ways to make it more usable. As I have gotten older, I think that my inclination to be useful to society has gotten stronger. If we do nothing, Japan’s information outbound transmission is going to fall increasingly behind. Even if the accuracy of current machine translation is insufficient, it is far better than not having it at all. Therefore, I am always striving to improve this,” says Professor Isahara.

I want to be optimistic about how much we can contribute to machine translation technology innovation, through the framework that Professor Isahara presents and through crowdsourcing, with the power of social communities brought to life by science.

References

- Hitoshi Isahara et al. (2014). ISO Language Resource Management Technical Specification Proposal for Controlled Natural Language: Basic Concepts and General Principles, Fourth Workshop on Controlled Natural Language (CNL 2014).

- Takako Aikawa, Kentaro Yamamoto, and Hitoshi Isahara. (2012). The Impact of Crowdsourcing Post-editing with Collaborative Translation Framework, JapTAL2012, pp.1-10.

- Hitoshi Isahara. (2012). Toward Practical Use of Machine Translation, JapTAL2012, pp.23-27.

- Midori Tatsumi, Anthony Hartley, Hitoshi Isahara, Kyo Kageura, Toshio Okamoto, Katsumasa Shimizu. (2012). Building Translation Awareness in Occasional Authors: A User Case from Japan, 16th Annual Conference on the European Association for Machine Translation (EAMT2012), pp.53-56.

- Anthony Hartley, Midori Tatsumi, Hitoshi Isahara, Kyo Kageura, Rei Miyata. (2012). Readability and Translatability Judgments for “Controlled Japanese”, 16th Annual Conference on the European Association for Machine Translation (EAMT2012), pp.237-244.

機械翻訳の精度向上に向け、

手法開発としくみ構築に取り組む

機械翻訳の技術は年々進歩を遂げ、ここへきて、ビッグデータ技術の進展を背景に、さらなる精度の向上に大きな期待が寄せられている。しかし一方で、欧米言語間の機械翻訳は実用レベルで活用されているのに対して、日本語から他言語への機械翻訳にはまだ多くの課題が残る。その課題を克服しようと、1980年代から機械翻訳の研究に従事してきた井佐原均教授に、先端の機械翻訳研究について聞いた。

日本語翻訳がうまくいかない理由

井佐原均教授は、通商産業省工業技術院電子技術総合研究所、郵政省通信総合研究所(現・情報通信研究機構:NICT)を経て、2010年からは豊橋技科大において、一貫して機械翻訳の研究に従事してきた。

「日本語から中国語、タイ語、マレーシア語、インドネシア語への機械翻訳や、日本語の話し言葉のデータベースの構築、日中・中日言語処理技術の開発研究など、さまざまな研究を手がけてきました。ただ、残念なことに、日本語からその他言語への機械翻訳の精度は向上してきたとはいえ、まだまだ不十分です。たとえば日英翻訳なら、語順の違いに加え、主語省略など、文脈に依存する日本語特有の性質が障壁となっています。情報発信のための翻訳であればなおのこと、品質を十分に担保しなければなりませんが、現実には機械翻訳システムの出力をそのまま使えるレベルにありません。実用化のためには、さまざまな工夫を凝らす必要があります」と井佐原教授は言う。

実は80年代、機械翻訳研究は日本が先行していた。大学などの公的研究機関に加え、多くの大手電機メーカーが機械翻訳システムの開発に参入したが、やがてほとんどの企業が撤退してしまう。その原因は、「サービス」を提供するという意識が足りなかったことにあると井佐原教授は指摘する。技術開発の過渡期にある機械翻訳の場合、一度、システムを構築してパッケージ化して売ればいいという従来型の製品提供では、ユーザを満足させることはできなかった。

「日本では情報を文書化して再利用するという発想が少ないことに加え、システムを発展させつつ、サービスを続けていくためのしくみが整っていませんでした。プロの翻訳者であっても、その分野に通じていることや事前知識は欠かせませんよね。同様に、機械翻訳においても翻訳エンジンの精度向上に加えて、使うことを前提としたデータベースの構築や更新、手法の開発、しくみづくりが欠かせないのです」(井佐原教授)

機械翻訳に必要な3つのステップ

そうした中、井佐原教授が、機械翻訳を用いた翻訳プロセスに不可欠な要素として挙げるのが、以下の三つである。①翻訳しやすい日本語の作成、②分野に応じた最適な用語の抽出、③後編集のしくみの構築だ。

「まず①の日本語の入力文を翻訳しやすいようにコントロールするだけでも、かなり効果があります。そこで、日本語の品質を落とすことなく、どのような入力文をつくれば機械翻訳がうまくいくのか、研究してきました」

その検証のため、地元企業に協力を仰ぎ、社内のマニュアルをルールに従って翻訳しやすい日本語、いわゆる「制限言語」に書き換えてもらい、翻訳精度を測る実験も行った。ルールは、主語や目的語をできるだけ省略しない、長文にしないといったもので、さほど煩雑なものではない。こうした研究の動きを背景に、現在、制限言語の必要性から、国際標準化機構(International Organization for Standardization:略称ISO)でも国際標準化が進められているところだ。

②の用語の抽出とは、その分野に関する大量の文書を蓄積し、その中から半自動的に、よく使われる「長めの語句」を抽出していくのである。「たとえば、『地球温暖化における二酸化炭素の影響』や『パイプラインにおける亀裂発生時のガス減圧特性』といった語句です。それらを自動的に抽出し、分野に通じた人が精査し、適切な対訳の用語集をあらかじめ用意しておくわけです」

最後は③の後編集だが、ここで井佐原教授らが取り入れたのがクラウドソーシングである。現状は後編集をして、翻訳文を整えなければ完璧な文書にはならない。ただし、プロの翻訳者に頼むと相当なコストがかかる。そこで効率化のために、プロの翻訳者ではないが、それなりにその分野に通じている人々にボランティアベースで作業をしてもらうわけだ。実際に、豊橋技科大のホームページ(英文)に機械翻訳のためのエンジンと編集ツールを搭載して、留学生に後編集をしてもらったところ、精度のいい翻訳ができることがわかった。

「うちの留学生であれば、本学のことはよく知っていますし、品質もそれなりにコントロールできます。たとえば、英語からインドネシア語に機械翻訳された文を数人で連携しながら直していくのですが、最終的にはプロの翻訳家の文章に近い精度に仕上げることができました」(井佐原教授)

分野ごとのコミュニティに参加を促す

現状、ビジネスの現場では、翻訳は一からプロの翻訳家に委ねることがほとんどだが、機械翻訳を入れるメリットは精度はそこそこでも、コストをかけずにスピードアップを図れることにある。今後、グローバル化や、外国人観光客の誘致などインバウンド市場の活性化を背景に、情報発信のための機械翻訳への期待はますます高まっていくだろう。

「たとえば、2019年に日本で開催が予定されているラグビーW杯に向けて、今後、どんどん日本語の記事がアップされていくでしょう。その際に、ラグビーファンによる後編集ができれば、かなり使える英語で情報発信できると期待しています。その翻訳結果を蓄積して学習することにより、さらに翻訳の精度を上げることもできます。とくに知識や能力があり、社会貢献をしたいと思っていらっしゃるシニア層の方に、クラウドソーシングに参加していただけたらと嬉しいですね。もっともボランティアとはいえ、貢献度に応じて有名選手のサインがもらえるなど、なんらかのインセンティブを用意する必要はあるでしょう」と井佐原教授。すでに、ラグビー記事の翻訳については、豊橋技科大と立教大学、NICTによる共同研究がスタートしている。

今後は、鉄道、カメラ、ラーメンなど、さまざまな分野のボランティア・ネットワークによる、日本語から英語への情報発信へと発展させていきたいという。さらには、IT企業と組んで、ビジネス分野でのマニュアル等のデータベースの共有化も視野に入れる。日本マイクロソフト株式会社や株式会社ブロードバンドタワーとの共同プロジェクトも始まった。日英翻訳を端緒にさまざまな言語への翻訳が広がり、新たな国際コミュニティが構築できるのではないかと、井佐原教授は展望を語る。品質の保証などの課題はあるものの、機械翻訳を社会に役立てるために、井佐原教授の奔走は続く。

取材・文=田井中麻都佳

取材後記

井佐原教授は、自然言語処理から始まって、長く翻訳エンジンの研究を手がけてきた。現在は用語の抽出や実用化へ向けた枠組みづくりなど、より実社会に根ざした取り組みへと研究をシフトさせている。「ずっと日本語の機械翻訳に携わってきて、もっと使えるものにしたいと思い続けてきました。歳とともに、社会の役に立ちたいという気持ちも強くなっていったように思います。このままでは日本の情報発信はますます遅れをとってしまう。現状の機械翻訳の精度が十分でなかったとしても、ないよりははるかにマシですからね。そのためにできることを考えているのです」と、井佐原教授。

井佐原教授が提示する枠組みとともに、一般の人の力を科学に生かすクラウドソーシングが、今後どこまで機械翻訳の技術革新に貢献できるのか、大いに期待したい。

Researcher Profile

Dr. Hitoshi Isahara studied natural language processing until Master level at Kyoto University. After graduation, he was engaged in research for machine translation and natural language processing, then received PhD (Engineering) in 1995. He held following various important posts: President of Asia-Pacific Association for Machine Translation and President of International Association for Machine Translation. These achievements were recognized, then he has been appointed to conference ambassador by Japan National Tourism Organization in 2015. Currently, Dr. Isahara is a Director of the Information and Media Center at Toyohashi University of Technology. His research interests are Machine translation, Lexical semantics, and Association by human.

Reporter Profile

Madoka Tainaka is a freelance editor, writer and interpreter. She graduated in Law from Chuo University, Japan. She served as a chief editor of “Nature Interface” magazine, a committee for the promotion of Information and Science Technology at MEXT (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology).

ここでコンテンツ終わりです。